Solomon Ndondo, a GFC fellow and the Executive Director of grassroots organization Africa Rise Foundation, discusses donor tendencies that hinder local partners’ effectiveness and proposes solutions as he reimagines the funder-partner relationship.

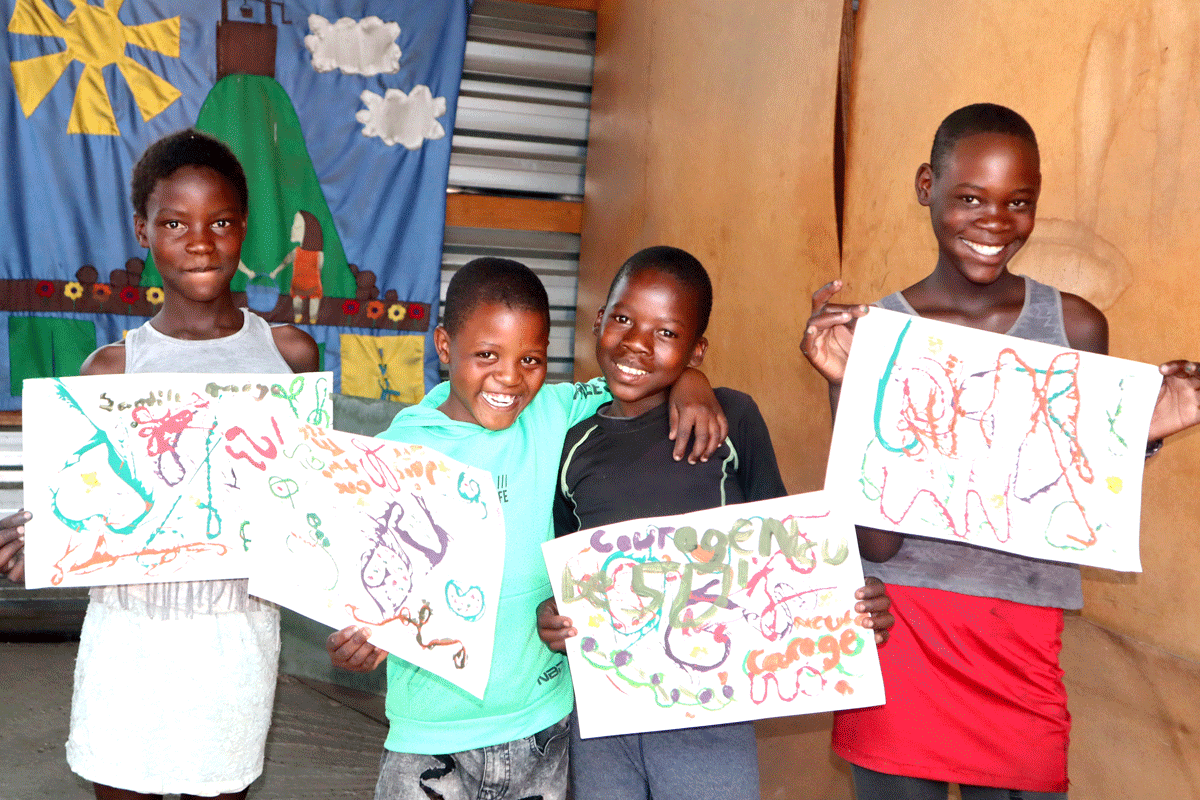

As the founder of Africa Rise Foundation (ARF) in Zimbabwe, which works on children’s rights and youth economic empowerment, I know that people at the community level can solve their own problems if they get the right support. For example, when ARF brought young people together to discuss solutions to the economic problems they encounter, they brainstormed ideas for projects they were passionate about doing. ARF then applied for the necessary tools from Tools with a Mission, and these successful projects are still ongoing. If donors come in as equal partners and allow the implementers or communities to set the agenda, real change is possible.

I have observed Global Fund for Children empowering local partners and ensuring that decision-making power lies with grassroots leaders and youth. With some of their other funders, however, GFC’s partners continue to face issues that hinder their creativity and effectiveness.

Below are a few of the major problems and some promising solutions.

Red tape in applications and reporting

Grassroots organizations face many challenges when they apply for funding and report on their progress. Due to minimal funds for salaries, organizations often have skeletal staff who are overwhelmed with responsibilities, with one person performing two or more positions. Some community leaders have described spending most of their time in the office with donor paperwork instead of in communities with young people. In response, some donors are experimenting with flexible applications and reporting, such as videos and phone calls, and use of local languages.

Donors focusing on projects rather than organizations

Donors tend to fund only a particular project, not an organization holistically. As the founder of ARF, I have had to divide my attention between projects, applying for grants, and other jobs to make ends meet. Project-based funding does not cover key staff who ensure the smooth running of the organization or even important supplies. One community leader said she worked with a donor who was demanding pictures taken by high-quality cameras while they were using smartphones due to a lack of resources. The donor’s grant did not support buying equipment. Investing in operating costs and strengthening the capacity of organizations plays a role in long-term change, rather than simply supporting the implementation of short-term projects.

Shifting power to the grassroots

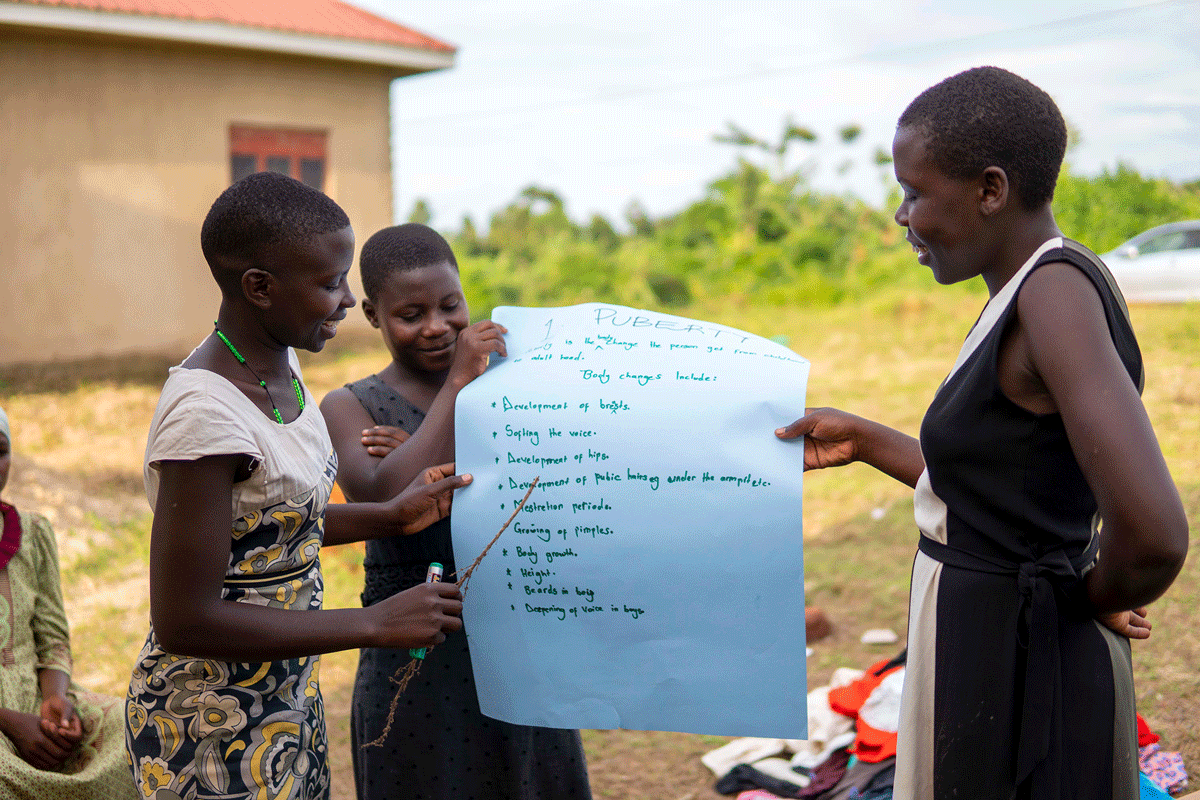

When donors shift power to the grassroots, people have the resources to solve issues affecting their communities. One way to shift power is through participatory grantmaking. With the launch of GFC’s Spark Fund, young people got decision-making power about funding in their geographical region, resulting in the selection of diverse issue areas and organizations reflecting the uniqueness of young people’s priorities throughout the world. As someone from Africa, it was great to see youth from my country and region making funding decisions about issues in our communities.

Donors avoiding being first funders

Most donors are hesitant to be an organization’s first funder. One organization in Southern Africa that received funding through the Spark Fund was really surprised that GFC did not require audit reports or previous external funding, typical prerequisites for other funders. While funders may see their financial investment as risky, grassroots leaders take even greater risks, at times imperiling their lives, freedom, and mental health. For instance, when ARF responded to COVID-19 in Zimbabwe in 2020, I was detained for hours for breaking lockdown rules while serving children from child-headed families who needed our support. First funding is what these leaders need to grow their organizations and implement their creative ideas.

Flexibility in funding guidelines

When donors are flexible, organizations are able to innovate and to discuss challenges and opportunities as they arise. One grassroots leader said that flexible funding from GFC enabled their organization to use art in its activism, while some other donors view art as solely entertainment, not as a force for good. The Trust-Based Philanthropy Project reports that while most funders became flexible during the COVID-19 pandemic, some are now going back to being strict. However, most of the issues that local partners work on are longtime crises that deserve the same flexibility from funders as the COVID-19 crisis.

Uneven investment within countries and among countries

Due to economic and political instability, my country of Zimbabwe is a no-go area for most donors, who see it as too risky. Some funders only focus on organizations in urban areas of a country, because they are easier to get to. Other funders only invest in organizations in South Africa but claim they serve the whole Southern Africa region. One way for donors to support more communities in need is to start with small investments such as the Spark Fund.

Communities setting agendas, not funders

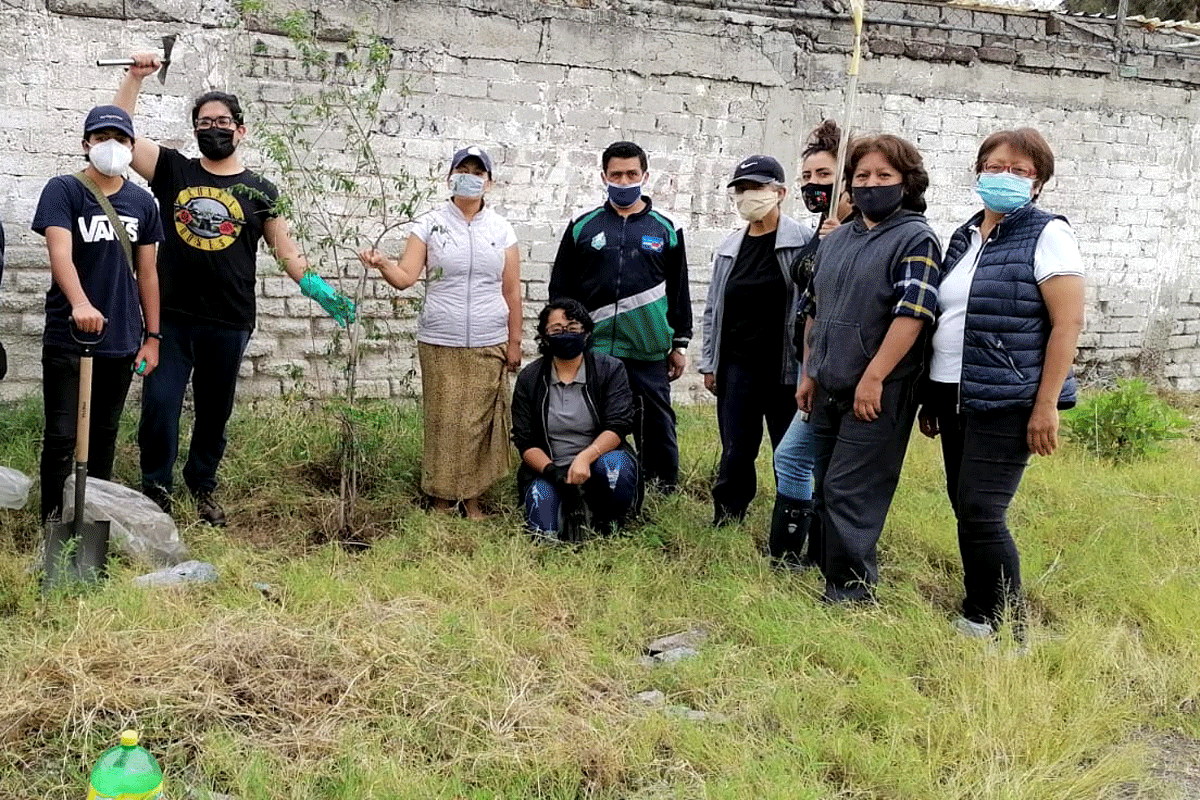

Donors come with their own way of doing things, which at times does not work in particular settings. While social change takes time, donors give grantee partners a short time to show results, prioritizing the number of participants over the quality of the change. In most cases, there is no room to discuss what is and is not possible. GFC and its partners in Sierra Leone followed Tostan’s community-led strategy and saw great outcomes, such as the community taking charge to build its own school and gain access to electricity and clean water.

To achieve real change in societies, donors and community organizations need to work together as equal partners. Change is only sustainable when it’s owned by those affected by an issue, and this is only possible when funding relationships are equitable.

Header photo: Community leaders who work with GFC posing for a photo. © GFC