This blog was written by Keyla Naomy Canales Rodríguez, a leader of the Girls Lead program at Organization for Youth Empowerment (OYE), a GFC partner in Honduras. This post is also available in Spanish.

Do you know what it is to live in fear? To look over your shoulder all the time, to hold your breath, to count your footsteps, to always be ready to run? That is no life at all.

In the face of fear, you have to choose: either you can be quiet, pretend that nothing is happening and think that violence is a woman’s destiny, or you can yell “I’ve had it up to here!” and “It’s not fair!” and you can try to change your life, for you and for other girls. I chose the second option.

My name is Keyla. I am 24 years old and I live in El Progreso, Honduras. Our town is famous for three things: a bridge called La Democracia, which is always broken, like our country; the banana fields; and the intense heat.

I still remember when I was a little girl and I could play outside with my friends: that feeling of freedom that I felt, how happy I was playing with my neighbors. We were a community. A family.

Then the mara showed up and everything changed. With the maras, fear spread. Now, if you were a woman or a girl you had to live locked up. Look down if a group of men approached and put up with the harassment. And be grateful every day just for being alive.

I was still a child, but I kept thinking: This is not fair. This has to change. So when they asked me the typical question: what do you want to be when you grow up? I had no doubts in my heart: I want to be a lawyer, to help others. Especially women. I want to change what is not fair.

For me, studying at university seemed like an impossible dream. Not only because we were poor, but because even my own social circle seemed to want to condemn me to a life of servitude. “Don’t worry about studying, better find yourself a good man and have children. If you want to study as a hobby that’s fine, but remember that a woman’s life plan should be to get married, have children, and take care of the home.”

I felt so angry! I just kept thinking: it’s not fair. It’s not fair that being a woman and being poor always put you at a disadvantage. We all have the right to study, to dream, to live without fear. And I did not come into this world to conform or to please anyone.

Thanks to my sister, I met an organization called Organization for Youth Empowerment (OYE), which supported me with a scholarship to continue my studies. This would have been enough, but OYE gave me much more. It gave me a purpose in life.

At OYE, they taught me that young people like myself can be leaders and agents of change in our communities. That we as girls and young women can get together and demand our rights. That I have the right to know and protect my body. That we carry limits and fears inside, and that the best way to combat them is to not remain silent.

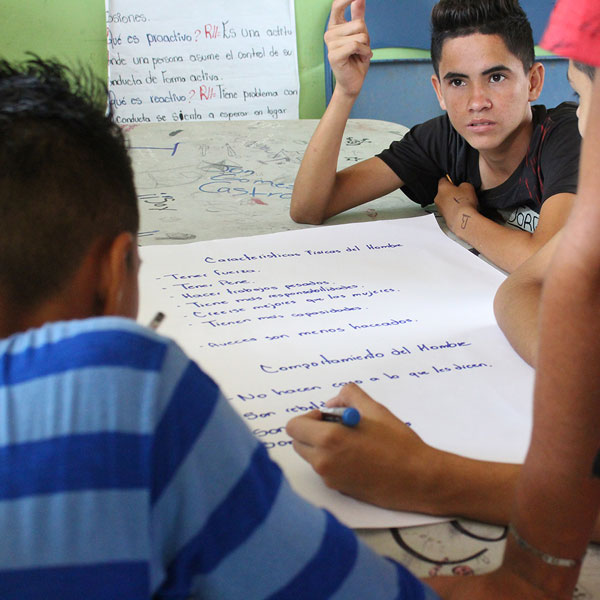

One of my first activities at OYE was to coordinate a program called “Sports in Action,” which sought, through sports, to promote more equitable relationships between young men and women to break down gender barriers and stereotypes.

Many people were surprised. There were even some who got angry.“How is this possible! A woman coordinating sports and organizing soccer tournaments. She should be teaching cooking or volleyball; those are women’s issues. She’s going to hurt himself, poor thing.”

It’s not fair. Again and again, it is not fair. But with achievements I showed them that women can practice any sport and lead sporting events. Even better than men.

Time passed and I was offered to coordinate a new program called Las Niñas Lideran (Girls Lead). The objective was to organize a group of girls so they could reflect on the gender violence they experience every day and on their sexual and reproductive health. We turned all these reflections into public policy recommendations, since we wanted the voices of girls and young women to be included in the decisions that the government makes and that affect our bodies and lives.

This program changed my life. I was able to learn so much from them … to get angry and be moved by their stories of harassment. To get outraged at the violence they suffer every day, to marvel at their clarity and their ability to make decisions. To admire their tenacity and courage. These girls have been the best teachers I’ve ever had.

I saw myself in them and it revived the violence I experienced. Again I felt anger. Again I felt outraged. But now, I knew I was not alone, and that gave me a lot of strength. I had recovered my community. I had found a family.

Despite hard times, we never allowed ourselves to lose hope. We sustained ourselves and reminded ourselves that joy must be defended. That without dance, without games, without creativity, we cannot change the world. If we stop laughing, we already lost.

It was in this space that I began to recognize myself as a young feminist woman. That was my purpose. I had lost my fear.

We took it to the streets. Without asking for permission. We went to schools, parks, government centers. We screamed, again and again: “We’ve had it up to here! It is not fair. We do not want and we do not deserve your violence and discrimination. And we are not willing to accept it.”

Speaking, screaming, claiming, we forced them to listen. And last year, we presented a draft of public policy on comprehensive sexual health to the municipal government. Our anger turned into action. Our outrage became a proposal.

We reflect together. We learn and teach. We lead. We show everyone that women are capable of doing great things. And by doing so, we transform the world.

And this is just the beginning.

Much remains to be done: we must continue to create spaces for men and women to reflect on the violence we see, experience and reproduce and realize that we have the power to change and improve our communities.

Violence affects us differently. So it is important to dialogue. To recognize that, although we are different, we have the same rights.

Now I am a lawyer and, while I am still connected to OYE in many ways, I actively work in a human rights organization. I fulfilled the dream of my life.

OYE taught me that I have a voice, and that that voice is worth a lot and can inspire others. That we must always set an example and always think about collective wellbeing. And that, if necessary, you have to scream. Scream until someone else hears you.

Never more. You will never have the comfort of my silence again. Over and over I will keep saying “It’s not fair – this has to change.”

That is the first step in making this world a better place.

Organization for Youth Empowerment (OYE) is building a generation of educated young leaders in Honduras who are committed to improving their communities. Its competitive scholarship program gives promising young people the support they need to graduate from university. Meanwhile, OYE scholars engage and educate their peers through youth-led projects that include a radio station, a magazine, public arts, and team sports.

The Girls Lead initiative supports leaders around the world, empowering adolescent girls to defend and exercise their rights.

The initiative is made up of 20 young women who participate in dialogue circles to promote open discussion and reflection on issues that impact their health and wellbeing. Participants also advocate for comprehensive sexuality education in local educational centers.

Through this program, OYE is currently seeking the approval of a municipal public policy related to comprehensive sexuality education in schools, with the aim of reducing El Progreso’s rate of teenage pregnancy, one of the highest in the country.