Gender justice

Gender justice, Safety and wellbeing, Youth power

In the past year, migratory patterns and demographics have changed significantly along the Central American, Mexican, and US corridor. As a new, highly visible migratory trend in the region, the caravans have exposed the violent context of the migrant’s journey – from their desperation to flee their home countries, to the human rights violations they encounter in transit and after they reach their destinations.

In this special feature, Global Fund for Children provides an overview of the caravans and examines recent changes in migratory demographics, such as the rising tide of women, families, and children on the move. We also highlight the needs and actions of migrant girls, and specifically how our local partners in Central America, Mexico, and the US are responding to this unfolding humanitarian crisis.

Click on the links below to jump to different topics within the report.

Read an introduction to our transnational initiative to protect the safety and rights of adolescent migrant girls.

Learn why migrants are moving in caravans, who is involved, and how their movements are impacting policies and attitudes in the region.

Review insights from our network of civil society organizations (CSOs) – what direct services the network provides, how we’re building collective impact, and how we’re strengthening the agency of migrant girls.

Learn how we’re helping our partners to develop their capacity and confront new challenges and opportunities.

Contributors to this report include Rodrigo Barraza, Marco Antonio Blanco, Elise Derstine, and Vanessa Stevens.

The Adolescent Girls and Migration Project, a partnership between the NoVo Foundation and Global Fund for Children, and with additional support from the Harold Simmons Foundation, supports a cohort of 11 civil society organizations that are committed, each in their own way, to protecting the safety and rights of adolescent migrant girls in Central America, Mexico, and the United States. The three-year project also focuses on raising public awareness on the challenges and heightened vulnerability these girls face throughout the stages of their journey.

Based along the migration path, these local partners provide services to migrant girls journeying north, girls who have been detained, and/or girls who choose to remain in Mexico. The project also includes partners based in the United States that help migrant girls who have recently arrived, have been detained, or are adjusting to a new life in the United States.

In this section we look at why migrants are moving in caravans, who is involved, and how their movements are impacting attitudes and politics in the region.

For decades, migratory flows from Central America have been a result of a variety of push-and-pull factors, such as civil conflict, poverty, social marginalization, lack of access to education and health services, family reunification, corruption, remittances, and a dearth of economic opportunities.

The phrase “in search of a better life” is often used to refer to these factors, all of which indeed remain critical for migrants, but recent changes suggest that people are fleeing not for a better life, but to survive.

Today, more women, unaccompanied children, and families are risking the dangerous 3,000-mile route. In 2018, the US Customs and Border Protection agency reported an increase of family units and unaccompanied children crossing the border, comprising roughly 47% of the apprehensions along the southwestern US border. Approximately 163,000 family members were apprehended last year – more than three times as many as in 2017, and the highest recorded number since 2012. In Yuma, Arizona, where migrants were once mostly comprised of farm workers and laborers, nearly 90% of border crossers are families, many of whom are seeking asylum as they flee violence in their home countries.

These demographic changes reflect the violent reality within Central America, particularly due to the growing incursion of international gangs known as “maras” and drug cartels. These violent groups afflict communities with increased rates of human trafficking, prostitution, drug trade, extortion, murder, and money laundering. According to data from the United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime, El Salvador has the highest homicide rate in the world (at 82.8 murders per 10,000 people), Honduras the second highest (at 56.5), and Guatemala the tenth (at 27.3).

“Maras” are also linked to, but not the only perpetrators responsible for, the growing rate of femicide in the region. Latin America is home to seven out of ten countries with the highest female murder rate, according to a 2015 study. El Salvador, Colombia, and Guatemala lead the list: El Salvador has a rate of 8.9 homicides per 100,000 women, Colombia a rate of 6.3, and Guatemala 6.2.

Traveling alone across Central America, Mexico, and the United States leads to increased vulnerability, risks, and sexual and gender-based violence (SGBV). This is particularly true for women, children, and LGBTQ migrants.

According to a 2017 study conducted by Kids in Need of Defense and Fray Matías de Córdova Human Rights Center, children in transit are at a greater risk for sexual harassment, rape, human trafficking, and coerced survival sex; the most vulnerable are girls and LGBTQ children and youth. Perpetrators of SGBV violence include organized criminal groups, smugglers and traffickers, immigration officials, authorities, and other migrants.

Violence is a risk women and children face at home, as well as on their journey. In the same KIND study, 70% of female participants who had experienced SGBV in their home countries reported that it was a key deciding factor for migrating. SGBV victims that are repatriated suffer continued, often worse forms of assault, rape, and SGBV.

In response to the violence in their home communities and to protect themselves in transit, migrants are seeking safety in numbers. In October alone, a caravan leaving San Pedro Sula, Honduras, was estimated to range from 3,000 to 5,000 migrants traveling together.

The caravans also provide increased visibility for migrants and their plight, allowing them to be seen not just as victims, but as advocates capable of raising awareness about the violence they suffer. Migrants have historically been reluctant to speak up to authority figures in defense of their rights, out of a fear of arrest or detention. Some hesitate to confide in advocacy groups out of fear that the exposure may also lead to detention.

This remains true today, but by traveling together, migrants are better positioned to question and denounce immigration authorities and unjust policies implemented in the region, whether in Guatemala, Mexico, or the US. Their heightened visibility as a group makes it easier for advocacy groups, CSOs, and nongovernmental organizations (NGOs) to gather information about their experiences and take direct action to address injustices and needs.

Unfortunately, migrants’ collective mobility also sparked a public backlash, and in many ways strengthened xenophobic and discriminatory attitudes. Many political figures and commentators portrayed the caravan as an invasion tactic, where alleged criminals and terrorists could co-opt the caravan in a Trojan Horse-like maneuver. This response further exposed the growing stigmatization and criminalization towards Central American and Mexican migrants and their defenders and supporters.

In October 2018, to cooperate with the US administration, the Mexican government temporarily closed its border with Guatemala, which resulted in violent protests and civil right violations that provoked an onslaught of global criticism.

In the US, the current administration has consistently advocated for regressive and hardline migration policies, such as increased border patrol and Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) surveillance, and the rolling back of refugee and asylum rights. The administration’s “zero tolerance” policy, for example, led to the forcible separation of more than 2,400 families at the US border; family separation continued even after the policy was revoked in the summer of 2018.

The US government has also announced that Temporary Protected Status is subject to expire for almost 400,000 immigrants by early 2020, which includes Salvadoran and Honduran residents who have lived in the US for nearly a decade. Human Rights Watch reports heightened levels of insecurity for non-citizens and stateless people, who have been more frequently detained by immigration authorities, including children and pregnant women, in the rapidly growing detention centers. Lastly, courts continue to debate the legality of the decision to end the Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals (DACA) program in 2017, leaving the fate of 800,000 young immigrants uncertain.

In early 2019, border security was the defining issue behind a 35-day US government shutdown, the longest in history. As of the writing of this report, President Donald Trump has declared a national emergency to build a wall along the Mexico-US border.

In response to this humanitarian crisis, GFC and its partners acted swiftly to meet the needs of the caravans of Central American migrants. The arrival of convoys of thousands of migrants presents distinct challenges for our partners, who provide a wide range of services and programs, and who must also prepare migrants to navigate the bureaucratic and legal processes at the borders’ ports of entry. In this section, we look at what kind of support they are providing, how they are collaborating with one another, and how they work to meet the needs of migrant girls.

Strategically located at both the Guatemala-Mexico border and the Mexico-US border, GFC partners directly provided more than 400 girls and boys with much-needed humanitarian aid, safety information, legal advice, counseling on immigration procedures, psychosocial support, and training on advocacy and youth empowerment from June to December 2018.

Humanitarian aid largely consisted of the provision of basic services and supplies for migrants, including shelter, food and water, hygiene supplies, and medical services. A few GFC partners noted a need to further integrate humanitarian assistance programs into their work with migrant children and adolescents. Located in Guatemala, our partner Jovenes por El Cambio took concrete steps by launching a successful fundraising campaign to offer more humanitarian aid to migrants.

Our local partners also play a role in advocacy efforts for migrants and relay information to key groups, such as journalists, media channels, human right centers, and legal clinics.

In Mexico, GFC partners have come together to report and denounce human right abuses. Fray Matías de Córdova Human Rights Center and Voces Mesoamericanas Acción con Pueblos Migrantes, along with several other organizations in Mexico and Guatemala, have launched a joint initiative called the “Humanitarian Brigade.” This new information-generating initiative allows partners to monitor human right abuses and escalate incidents with migrants, the cohort of partners, and news outlets.

In a similar fashion, Sin Fronteras has joined local authorities, international organizations, CSOs, and NGOs, along with the Comisión de Derechos Humanos del Distrito Federal (Mexico City Human Rights Commission), in a project called Puente Humanitario (Humanitarian Bridge). This project ensures migrants in the caravan have access to health services, food, and knowledge on migratory procedures in Mexico and the US. At the same time, the project raises awareness about the specific needs of migrant children and youth, promoting gender-focused interventions.

Before the Adolescent Girls and Migration Project, much of the work carried out by our partners was limited to their immediate communities. Over the past several months, the cohort of 11 partners has developed into a transnational network of grassroots organizations, civil society organizations, and refuge centers that together can provide more robust services for migrant youth. This is best showcased when partners have joined efforts at a regional and international level to offer complementary services and benefits for migrants in transition.

After the success of the first GFC convening in August 2018, several partners came together to offer more efficient and timely services in response to the migrant caravans and are expanding their work and knowledge across the affected region by working in direct collaboration with each other. GFC partners actively share their experiences and learning from each other via public platforms open to other agents, institutions, and advocates working to safeguard the rights of migrants in Central America, Mexico, and the US.

For example, given the increase in migrants of indigenous descent from Central America, Al Otro Lado (in the Tijuana/Los Angeles-area) collaborated with Fray Matías (in Chiapas, Mexico) and Colectivo Vida Digna (in Guatemala) to translate their current Know Your Rights materials into indigenous languages to ensure all migrants can access important information to protect their rights in seeking asylum and facing potential detention and family separation.

Vida Digna and Al Otro Lado are also collaborating across borders to help migrants prepare the necessary documentation to apply for refugee status and asylum in the United States. When possible, this legal process is initiated by Vida Digna in Guatemala and followed up by Al Otro Lado in Tijuana. Both organizations also work to ensure a dignified and rights-based return for deportees.

We commonly see men as the central actors in migratory flows, with women appearing in the periphery. Mainstream media about Central America and Mexican immigration often focus on migrant men, with much of this coverage aiming to vilify or cherry-pick stories to make deceptive generalizations. The stories of migrant women and girls go untold, including the horrendous SGBV violations that occur in transit from their home to host countries.

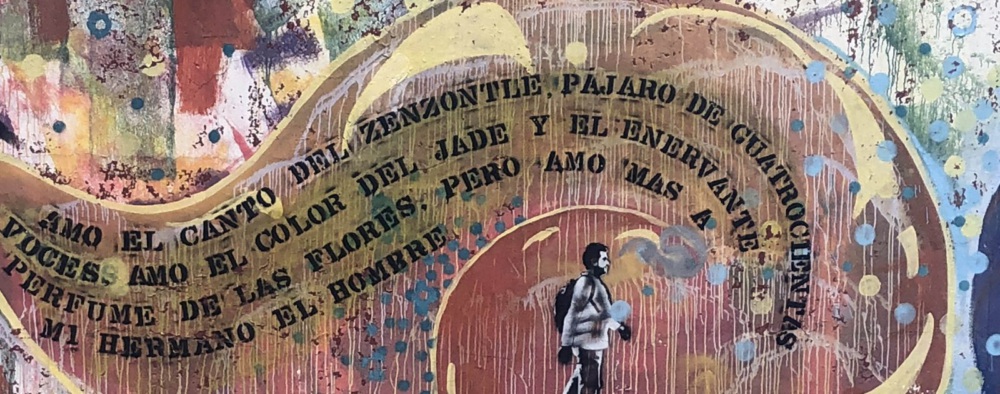

In reality, migrant girls and women are survivors of violence, political agents, and protagonists in the complex migratory dynamics of this challenging and constantly changing region.

One of the main objectives of the Adolescent Girls and Migration Project is to make visible the violence suffered by migrant girls and women every day, while empowering them to become agents and advocates with access to new strategies for intervention, collective organization, and resistance.

During 2018, we have helped our partners to develop and strengthen girl-centered and girl-led initiatives all across the region. Step by step, migrant girls are beginning to take a leading role in the decision-making processes of the organizations, community actions and interventions, and advocacy and communication strategies.

In 2018, more than 1,500 migrant girls and adolescents benefited directly from our partners’ activities and programs. Here are examples of specific initiatives that strengthen the agency of migrant girls and youth:

As border security continues to make headlines, our partners’ resolve to advance and protect the rights of migrant youth remains unshakable. At GFC, we’re planning numerous events and activities to support them in 2019: