Education

Education, Safety and wellbeing

When I am on the road, I frequently lament the lack of recycling bins in the hotels and homes where I stay, worrying that my many empty bottles of purified water are contributing to the world’s garbage problem. But almost everywhere I travel, there is a vast and complex recycling ecosystem in small town dumps and big city landfills.

Wastepicking is the most common form of recycling in much of the developing world. Though often viewed with disdain, it fulfills an important environmental function—keeping tons of waste out of landfills and replacing extraction of new raw material with low cost recycled materials in production.

It is also in an important income source for many people experiencing deep poverty.

In Chimalhuacan, Mexico, just outside the capital city, a group of wastepicker families has moved from a town dump that was shut down to a new landfill, resettling the hills just outside the gates, following the work they know.

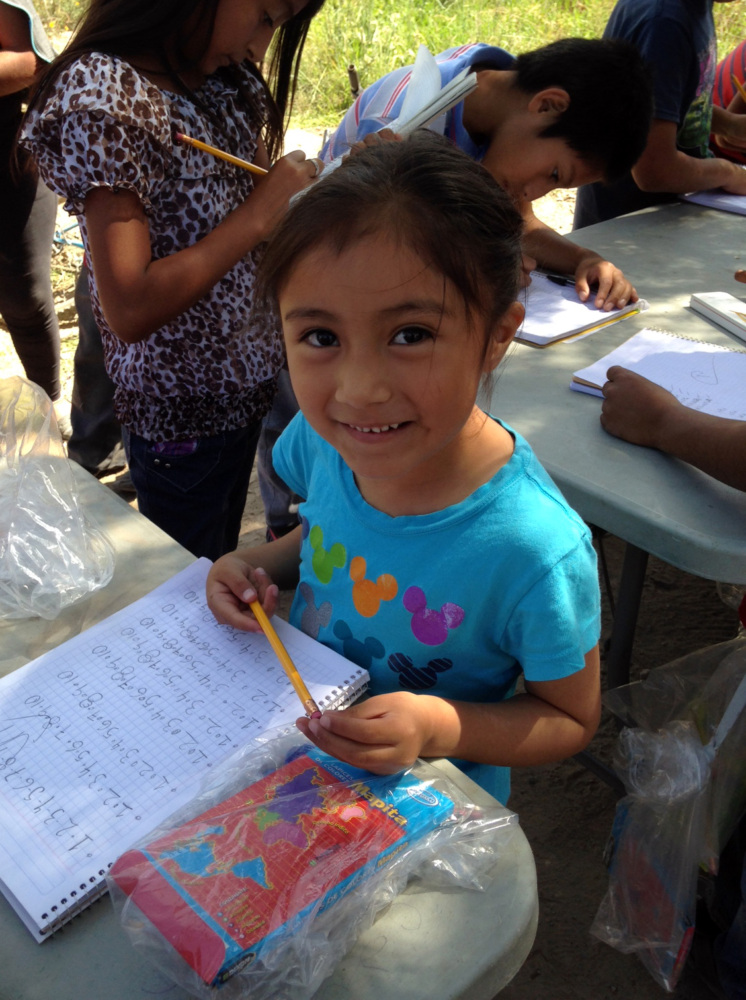

While wastepickers may be grateful for this work, most parents dream of a future for their children with more possibilities and less hardship. Over the past five years, our partner Alliance for Community Integration Utopía has designed, tested, assessed, and solidified a methodology for afterschool programming for children of wastepickers. Their activities strengthen reading and math skills using games and puzzles that the kids explore on their own with support of a trained teacher.

Utopía’s professional physical education teacher also teach kids to address conflict and practice self-discipline, fairness, and patience in pursuing goals through limalama, a Polynesian self-defense martial art. Limalama tournaments have allowed the children to travel beyond their small community and imagine other futures for themselves. Their academic performance has also improved, paving the way for those alternative futures to become reality.

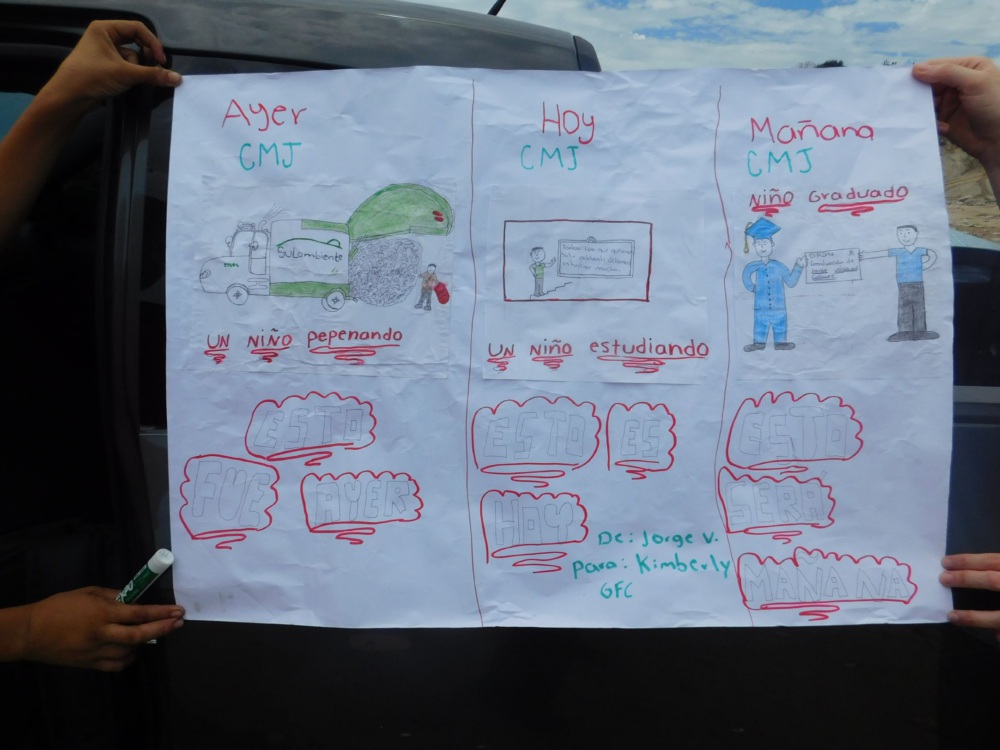

In Ocotillo, Cortés, Honduras, the Mixed Youth Cooperative (CMJ) faces an even greater challenge in the landfill that receives most of the waste from San Pedro Sula, Honduras’ second largest city.

Wastepicking in Ocotillo’s landfill may pay a meager piece-meal wage, but it still pays better than other unskilled jobs, as one mother of four told me. Argelia started collecting cardboard and nylon at the dump five years ago when she realized she could reliably bring home twice what she made doing laundry service out of her home.

CMJ’s worry, though, is that mothers like Argelia bring their children with them. In Ocotillo, toddlers play as their parents pick through the waste around them, and children help after school until they drop out, many before sixth grade, and come to work full time as adolescents.

They pull out bottles, cans, strips of cloth, nylon scraps, pieces of cardboard, specializing in one or two materials based their standings in the wastepicker hierarchy. Crews of adults, teenagers and kids as young as seven track each garbage truck that arrives, climbing onto new piles of garbage and fighting vultures to extract recyclable material, before jumping out of the way of heavy bulldozers.

Landfills are dangerous and unhealthy places for children, and in Ocotillo there are other risks too.

The landfill is owned by a company contracted by the municipal government, but the purchase of the materials that the wastepickers collect is managed by a powerful criminal gang. They set the prices and the rules for the wastepickers, and they enforce them violently when required.

Kids in this environment protect themselves by toughening up—boys and girls alike. Verbal attacks and denigration of girls and anyone perceived to be weak are almost constant, while physical fights are common when conflicts boil over. The gang targets young wastepicker girls and boys for recruitment, drug dealing and, in some cases, sexual exploitation.

Despite any income an adolescent might earn to support themselves or their families, the longer they spend in the landfill, the higher their chances of being forced or coerced into self-destructive criminal activity.

CMJ has responded to this complex challenge by giving adolescent wastepickers scholarships to return to school. The organization also brings them together outside the landfill for workshops on managing conflict and thinking differently about gender stereotypes and how they relate to each other.

CMJ has recruited two psychologists to cater a curriculum to the specific needs of these young people and hired a community leader, who is a former wastepicker herself, to provide regular follow up with each scholarship student. Thanks to another charity, the younger children can now attend a new elementary school just outside the gates of the landfill, keeping them safe and building the foundation for them to have other options when they are older.

It’s a slow process, but over time, children and youth spend less time in the landfill, away from the dangers of accidents, illness, violent conflict and gang recruitment, and more time exploring other paths for their lives.

Utopía’s Executive Director, Jesús Villallobos, and CMJ’s Program Coordinator, Ami Noél Martinez, met at a GFC regional convening in Managua, Nicaragua in 2017, and struck up an immediate friendship. In December they pitched in their own personal funds to pay for Ami Noel and CMJ’s Executive Director Jesús Santos to visit Utopía’s work in Mexico. Inspired by what they say, CMJ is working to enhance their own approach and replicate Utopía’s model. I was inspired by the power of creating spaces for knowledge exchange and building networks across organizations working towards the same goal.

At the end of my visit, I sat on a step eating a bologna and cheese sandwich with Axel, a teenager who, an hour before in CMJ’s workshop, I had jokingly chastised for calling me beautiful. He told me he started wastepicking at the dump when he was little, and that he made good money, but that he doesn’t have much time for it anymore. He’s studying now, and though he could still go to the dump after school like many of his classmates, he usually goes to work at a local woodshop instead. He wants to become a carpenter and even though he doesn’t make that much money as an apprentice, he likes it a lot and he knows he’ll earn more in the future.

Header photo: © APIC Utopia