Youth power

Education, Gender justice, Safety and wellbeing, Youth power

As adults, we often think that playing is a waste of time. Playing is for children, we tell ourselves. Who has time for such nonsense?

We live our lives believing that play is permitted only when we are young and, as we grow older, we resign ourselves to the inevitability of seriousness. Playing is, for many, incompatible with the adult world. And that is a huge mistake.

Those of us who work closely with children and young people often turn to games and dynamics as a way to break the ice. In these instances, without losing our adult-centric gaze, we think of play as a way to help people laugh and relax so that the things that really matter are more easily understood. Playing is still a means, a transition, a downtime.

But what if we look beyond this limited perspective? What if we see play as a path to recognize the value of emotions, build knowledge, and find collective solutions to social problems?

That is the essence of ludo-pedagogy, a critical and transformative tool that I fell in love with almost ten years ago and that always accompanies me in my work.

[image_caption caption=”Young Guatemalan women use play to learn about migration and human rights in Tapachula, Chiapas, Mexico. © Global Fund for Children” float=””]

[/image_caption]

Inspired by the Paulo Freire’s Popular Education methodology, ludo-pedagogy is a process of constant construction and reinvention. It is an approach based on the intersection of three areas: playing, discovering, and the collective construction of knowledge.

In the words of the Uruguayan Collective of Ludo-pedagogy, La Mancha: “playing allows us to question the obvious, to confront the truth, to challenge the established.”

As a long-term socio-educational process, ludo-pedagogy sees playing as a learning space that allows us to appropriate reality creatively, so that this reality is felt, thought, criticized, and transformed collectively.

As a methodology, ludo-pedagogy begins (and ends) in our bodies. By transforming our bodies, moving them in different ways, taking care of them, and connecting them with other bodies, we build sensations that allow us to look at reality with fresh eyes and to try other possibilities of relating to others. Our bodies allow us to build an emotional and caring space.

Playing with and from the body also allows us to recognize and be in touch with our deepest fears (to be ridiculed, to fail, to be observed) and, at the same time, it invites us to try to overcome these fears.

Playing allows us to touch, imagine, test, experience, know, disobey, transform, and create new languages from happiness, pleasure, and art. By playing, we transform the world, and we also transform ourselves.

However, in my experience, games – which generally emphasize tactics, rules, and goals – are often prioritized over play, which is more open-ended and exploratory. So, often in workshops or trainings, you just have a fun time or compete to win a prize and that’s it. Here are three tips to overcome these dangers and truly play to transform:

Learning does not happen in a vacuum – it is not about memorizing concepts, or starting from abstract situations, away from people. On the contrary, learning implies understanding how and in what ways reality affects our daily lives.

Playing, in that sense, has a double utility. It reminds us of stories, moments, situations, and emotions that we have experienced and that are familiar to us: laughter, memories that make us proud or ashamed, the feeling of what it was like to be a child. At the same time, playing opens new experiences on which we can reflect and learn.

Let’s introduce ourselves, let’s greet each other, let’s touch each other! This should be the start for any playing space. Let’s play to recognize who we are and to recognize ourselves in others. Celebrating diversity and, at the same time, finding common spaces that build a sense of community.

When playing, starting from a personal experience allows people to get truly involved and identify with the topics to be explored. To be fully present. In sharing our stories, we discover that we face similar violence and problems in our daily lives and communities and that, together, we can do something to confront and overcome these problems. That is the first step in understanding the world. And transforming it.

[image_caption caption=”Boys learn about gender masculinities through play in San Cristóbal, Chiapas, Mexico. © Global Fund for Children” float=””]

[/image_caption]

Playing opens a different space and time, because when playing, we leave behind our typical ways of interacting with and understanding the world. We leave behind the everyday as we enter a new and unknown dimension. That is why we must always play in large spaces, which we can upholster with new ideas, sounds, and creations.

When playing, everything should seem possible. It is the ideal space for creation: sounds, ideas, objects, personalities. Playing manipulates and transform reality.

The rupture of traditional everyday logic is what is known as “playful reality.” Each player must decide for themselves whether they play or not, and how far they want to go into this playful reality. It is impossible to force someone to play. We can only seduce them, provoke them, invite them to feel uncomfortable. And take care to thank that discomfort.

In the playful reality, the past, the present, and the future of people coexist and interact with each other. Playful reality is the space of chaos and uncertainty and, therefore, of creation and imagination. Here are three types of games that you can use to install this playful reality:

a) Those that allow movement, dynamism, the sensation of vertigo. Games that build a collective energy conducive to invention and affection. Pass the energy, create new sounds, act like an animal. Abandon yourself to connect with others.

b) Games that seek to break ridicule and shame. That allow us to recover our right to fail and realize that we are much more and can do much more than we think or what society may force us to believe. Act, sing, dance, make a fool of yourself … try something new to feel alive.

c) Games of introspection, a political exercise of memory that reminds us of who we are and where we come from, and that invites us to write our own history. Close your eyes, remember sensations, invoke ancestors … Honor your living memory.

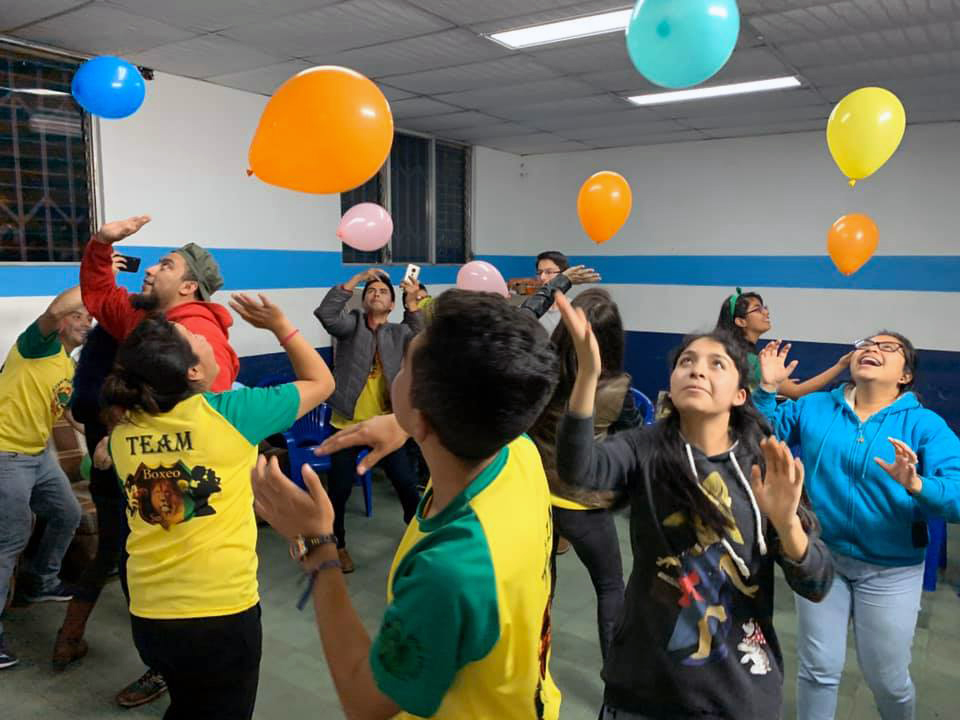

[image_caption caption=”Playing with balloons with GFC partner Jóvenes por El Cambio in San Marcos, Guatemala. © Global Fund for Children” float=””]

[/image_caption]

The facilitator creates rhythm between these games so that the sensations are genuine and spontaneous and the energy is in the right place. More importantly, the facilitator accompanies the participants so that they feel safe, recognizing their bravery and reminding them that they are not alone.

As facilitators, we must do everything possible to make this laboratory of playing as extended as possible, and to make sure playing is starting to gain space in everyday life. Setting aside homework and daily tasks, encouraging new encounters, reminding participants that playing is a political act of reinventing the world.

After immersing ourselves in the playful reality, we must step back and reflect on what happened. I recommend two types of evaluation for facilitators:

The “hot” evaluation, in which the games and proposals are reconstructed, recovering all the emotions, reflections, and ideas that have emerged. The main objective is to build a group memory where fears, nerves, laughs, tensions, and joys translate into a critical look at reality that challenges us in the individual and the collective. The question that should always guide this evaluation is: what did you notice? Thus, playing connects with reality.

A few days after the workshop, the facilitators should also meet to share their impressions about the group energy that was generated and the possible opportunities for improvement. This is called the strategic evaluation.

We reflect personally and collectively on our role, how we live it, what we want to improve, how to generate synergy in the team, and how to identify possibilities and next steps. We identify our mistakes, not to judge them, but to learn from them and enhance our commitment to social change.

The most important thing is to dare to play, to lose fear. To invite to play, by playing. And I am grateful every day that GFC partners, even working in contexts full of violence, injustice, and inequality, dare to use playing as a tool for social transformation and for the recovery and reinvention of our collective humanity.

And you?…

Do you want to play?