Justicia de género, seguridad y bienestar

Educación, justicia de género, poder juvenil

Me siento con las piernas cruzadas en el suelo de un alegre centro de primera infancia financiado por el gobierno, con paredes de color rosa. Acompaño al personal del programa Avaní, uno de los socios de GFC en Kolhapur, India, para una conversación en la que adolescentes, jóvenes mayores y adultos de una determinada aldea se están conociendo y compartiendo lo que consideran importante acerca de su comunidad. No hay fanfarria sobre mi presencia; simplemente soy un visitante que se suma a la conversación mientras nos presentamos y mencionamos algo que cada uno de nosotros aprecia del lugar donde vivimos.

Como entidad financiadora que ha defendido el papel de las organizaciones comunitarias desde su fundación hace 30 años, cuestionar algunas de las nociones predominantes en el desarrollo global es algo que llevamos en la sangre. Reconocemos que los complejos legados de las relaciones inequitativas con los financiadores en ciertas regiones pueden influir en la dinámica entre las organizaciones y las comunidades en las que están insertas. El personal de las organizaciones locales a veces ve los problemas de las comunidades con más intensidad que sus puntos fuertes y siente el deber de enseñar, capacitar o encontrar soluciones y “entregarlas”. Esta dinámica puede verse reforzada por los financiadores que acuden a las organizaciones con ideas ya desarrolladas para su implementación o insisten en que las organizaciones diseñen resultados que se lograrán al comienzo de una “intervención” sin una participación significativa de los miembros de la comunidad afectada.

Estos legados, en particular en África occidental y el sur de Asia, nos han llevado a invitar a los socios interesados a participar en procesos reflexivos para cuestionar los supuestos sobre lo que significa ser liderado por la comunidad. En la India, mi colega Rituu Nanda ha estado acompañando a varios de nuestros socios a través de El Proceso de Competencia para la Vida Comunitaria de la Constelación (CLCP), lo que fortalece su confianza como facilitadores de diálogos comunitarios para estimular la valoración de las fortalezas individuales; promover el diálogo entre diferentes grupos en las comunidades, como adolescentes y líderes locales; y fomentar un sentido de posibilidad de que los miembros de la comunidad puedan hacer cambios en sus propios términos.

En el proceso de abordar las causas profundas de las normas de género restrictivas, Avaní El equipo reconoció que, en lugar de trabajar únicamente con jóvenes, necesitaban profundizar en diálogos comunitarios como el que hemos participado. Al final de esta reunión, un grupo de estudiantes varones nos invita a visitar la pequeña biblioteca que han instalado a unas pocas cuadras de distancia en un espacio donado por una cooperativa local. Los estudiantes han reunido libros, organizado un espacio de escritorio para estudiar en silencio y desarrollado un sistema de préstamo de libros. Cuando preguntamos dónde están las mujeres, explican que los padres permiten que las niñas y las mujeres jóvenes saquen libros, pero no que estudien allí. Están pensando qué hacer para que las niñas y sus familias se sientan cómodas. Ninguna organización o donante está detrás de este esfuerzo: es un cambio liderado por la comunidad en acción.

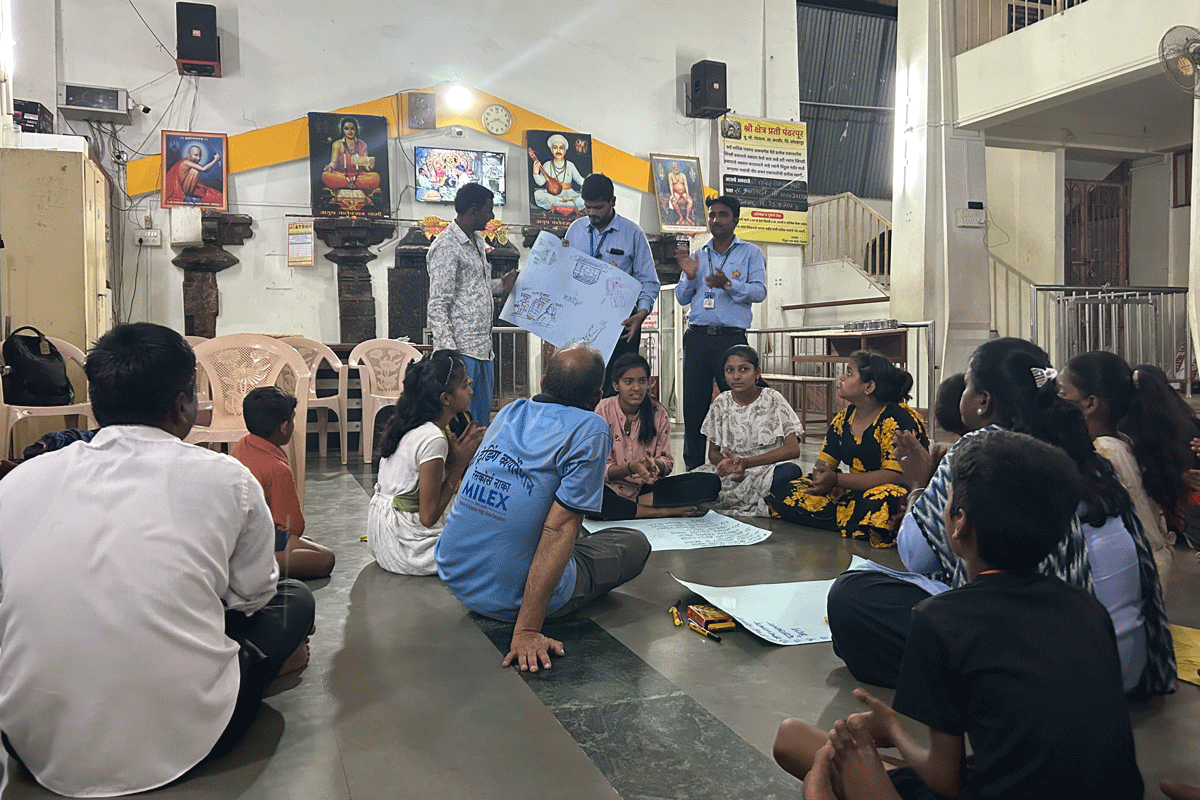

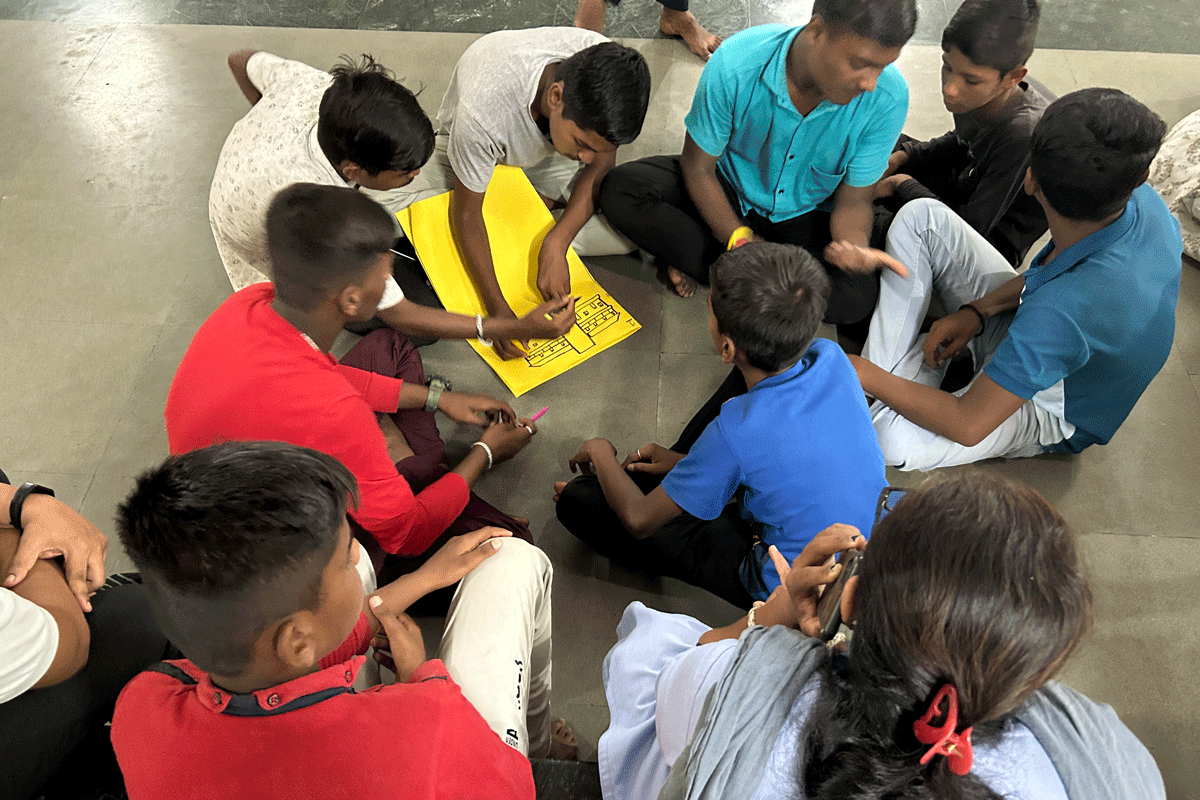

Al día siguiente, nos invitan a participar en una sesión de “construcción de sueños” en la que grupos de niños, niñas y líderes electos locales se reúnen un viernes por la noche en el espacio abierto cerca de la entrada de un templo hindú. Cada grupo dibuja con entusiasmo sus sueños para la comunidad y comparte el dibujo y sus elementos con todo el grupo. Los jóvenes están emocionados; han estado tratando de conseguir que los líderes locales asistan a una reunión con ellos durante casi un año, pero las elecciones lo hicieron complicado. Los jóvenes también comparten una obra de teatro que crearon anteriormente para llamar la atención sobre los efectos de las normas de género dañinas en las vidas de personas como ellos.

A principios de este año, tuve la oportunidad de acompañar a miembros del personal de los socios de GFC en Costa de Marfil y Guinea a Promoviendo el bienestar comunitario, un taller de diez días celebrado en Senegal por Tostán, una organización que trabaja desde hace 30 años para empoderar a las comunidades y generar cambios sociales. En este taller se compartieron las prácticas y los principios del trabajo de Tostan para estimular la reflexión sobre el papel de los miembros de la comunidad como líderes de su propio desarrollo y no como “beneficiarios” de proyectos.

El taller comenzó con todo el equipo del centro de capacitación de Tostan, desde los cocineros hasta los jardineros y los facilitadores, dando una alegre bienvenida al grupo y presentándose, transmitiendo el poderoso mensaje de que la voz de todos es importante. Esta filosofía se extiende a los aprendizajes que Tostan comparte sobre su experiencia de escuchar a los miembros de la comunidad y fomentar una "capacidad de aspirar" en lugar de venir a brindar capacitación o "sensibilizar" en función de lo que el personal o los donantes piensan que es importante. Desde este taller, mis colegas en la región, Amé Atsu David y Ramanou Babaedjou, han estado acompañando a nuestros socios para experimentar con el desempeño de un papel más facilitador y menos directivo en la forma en que involucran a las comunidades para impulsar el cambio en función de las propias prioridades de las comunidades.

Veo hilos comunes entretejidos en los esfuerzos por centrar a las comunidades en estas dos regiones. Nuestros socios en ambas regiones reconocen que están trabajando en ecosistemas que a menudo no son amigables con el proceso paciente y no lineal de fomentar el cambio liderado por la comunidad. Los ciclos de financiación a corto plazo, a veces tan breves como de seis meses, van en contra del tiempo necesario para generar confianza, escuchar, suscitar sueños y apoyar planes de acción. Las solicitudes de propuestas que piden indicadores específicos de cambio sin espacio para que los miembros de la comunidad definan ese cambio son otras barreras, y las organizaciones a menudo no sienten que sean capaces de negociar. Algunos socios compartieron historias de financiadores que dictan actividades específicas, como campañas de concienciación, que las organizaciones creen que son superficiales y no abordan dinámicas sociales más profundas.

Pasar tiempo con miembros de la comunidad en India y Senegal fortaleció mi convicción de que necesitamos entender cómo se relacionan nuestros socios con las comunidades en las que trabajan. Con el cambio impulsado por la comunidad como una de las estrellas guía en La visión de cinco años de GFCNo podemos ignorar cómo los legados coloniales en muchas regiones afectan la forma en que algunos de nuestros socios interactúan con las personas con las que trabajan.

Si bien reconocemos que otros financiadores que apoyan a nuestros socios pueden operar con diferentes limitaciones, podemos trabajar con nuestros socios para documentar mejor los cambios que tienen lugar cuando fortalecen sus habilidades de facilitación para trabajar con las comunidades, cuando realmente escuchan y cuando abordan cuestiones como la equidad de género de manera holística.

“Cuando nuestros socios puedan defender con más fuerza las transformaciones que se producen en sus propias vidas, en sus organizaciones y, lo más importante, en las comunidades con las que trabajan, tendrán herramientas más sólidas para influir en los demás y lograr que comprendan que centrar a las comunidades no es un concepto confuso, sino la clave para un cambio sostenible”. – Corey Oser, vicepresidente de programas

Foto de encabezado: Los socios de GFC en Costa de Marfil y Guinea interactúan con Demba Diawara, imán y jefe de la aldea de Simbara, quien ayudó a dar forma al modelo de Tostan.